If you invest in the stock of one company, you run the real risk of losing money. Not because the market value will go down, but because Chapter 11 could happen. That’s bankruptcy. Typically stock holders get nothing in bankruptcy. By the way, risk doesn’t mean it will happen, it just means there’s a higher likelihood of it happening.

So how do you mitigate (reduce) the risk of your one company going bankrupt? You invest in the stock of more than one company. Real risk is reduced for each new company you buy. Real risk is reduced quite a bit when you buy your second company but as you add more, the benefit declines quickly. The real risk is nearly the same when you own 20 companies as when you own 1000 (Kiplinger, Glassman).

Real Risk Versus Volatility

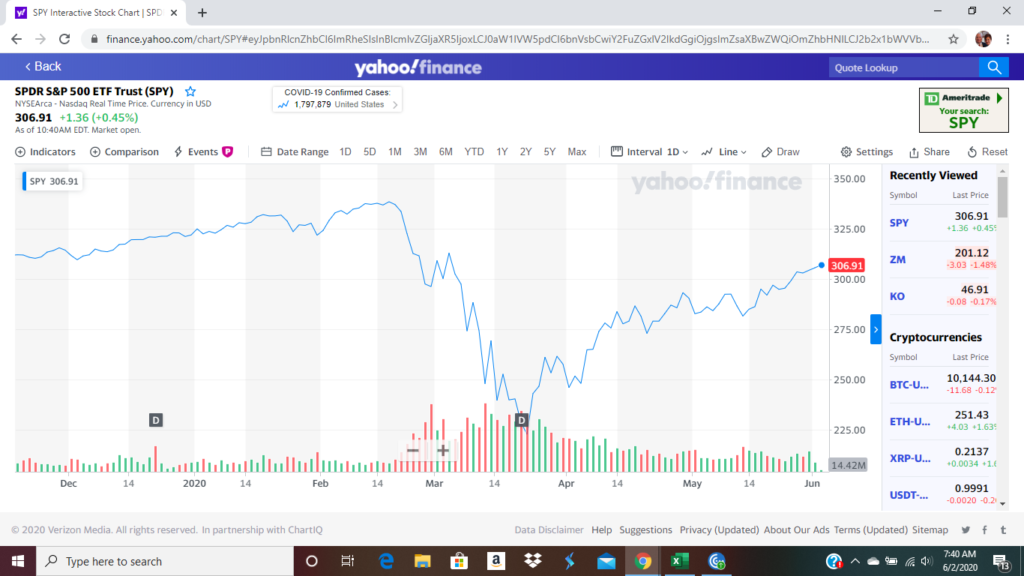

Here is a chart to understand volatility:

This is an index ETF over the S&P 500 index. The S&P 500 companies are generally worth the same on day one as day 365 (maybe worth a little more), but the market values them differently on different days. Sometimes the prices are up, sometimes the prices are down. Sometimes the whole market goes down or up. Notice that the SPY never went to zero because that would require all of the 500 S&P companies to go bankrupt at once.

Since the 500 companies will never, or virtually never, go bankrupt at once, we can say the real risk of SPY going to zero is virtually null. It is possible, but it likely will never happen. The possibility of any company in the S&P going bankrupt ever is virtually 100%. So if you were betting that no S&P company would ever go bankrupt you would probably lose. Any given S&P company going bankrupt is probably somewhere between 0 and 100%.

Real risk is the probability of losing real money in a stock, where volatility is the temporary market value changes of a stock.

Volatility because real risk when the investor reacts to market changes. So let’s say the market goes down abruptly and the investor sells his stock. He loses real money. If he would hold his stock instead, the market value would probably return to where it was. I think this is why volatility is often confused with risk.

The Difference Between 10 And 20 Companies

If 20 companies is nearly the same risk level as 1000 companies, why not invest in stocks of 20 companies? Well you could but you would have more companies to research and keep up with on a regular basis. And the risk benefit of owning double the companies is not double, it’s marginal. So more work, little benefit.

A Tale Of An S&P Company

Five companies now make up around 18% of the S&P 500 (Fortune, Carlson). One of them (*I own it*) had the best return over the past 5 years within the S&P, by far. Now the S&P is made up of large cap stocks that don’t move a whole lot, so perhaps the return wouldn’t impress you that much, but I believe it is nearly double the second place company.

If you would have owned these five companies you would have done well but not as well as you would have done with just the one. Still, with five you would have reduced your real risk significantly.

Fewer Companies, More Rewards, Less Work

Since returns vary so widely by company, fewer of the right companies will make you far more than more companies. And fewer companies will be less work to keep up with the information the company is putting out. It is seriously win-win. I really think that 10 companies is a good number.

More Reading: